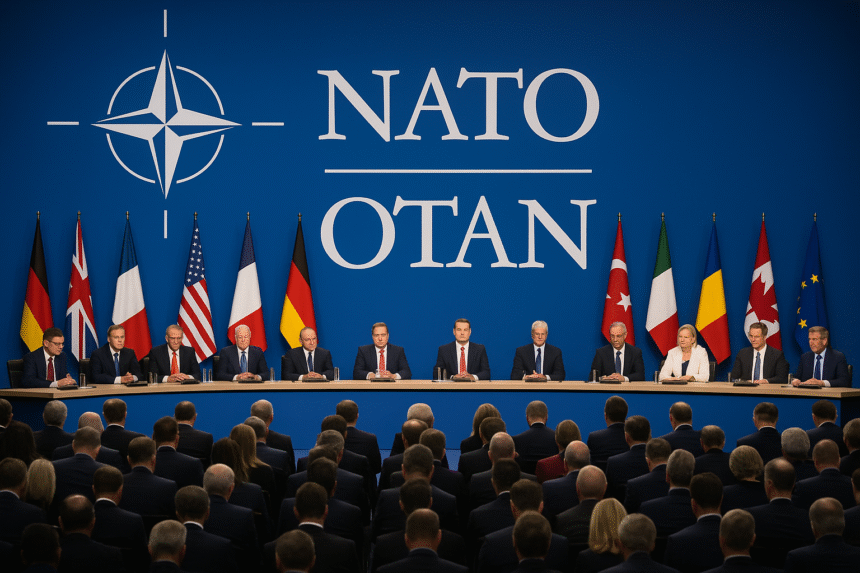

As NATO convenes this week in Washington to mark its 76th anniversary, the atmosphere is a cocktail of celebration and anxiety. With Ukraine’s war still raging, Russia resurgent, and the U.S. election looming, leaders of the 32-member alliance are asking the question aloud that has long simmered in closed-door meetings: Can NATO remain united in a world that no longer shares the same center of gravity?

This summit is not just a ritual. It is a reckoning.

The Resurgence That Masked Deeper Fault Lines

In the immediate aftermath of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022, NATO seemed to experience a renaissance. The alliance, long thought by some to be brain-dead (to quote President Macron in 2019), roared back to life. Defense budgets ballooned. Intelligence cooperation deepened. Finland and Sweden—two militarily capable and politically stable states—joined the alliance, marking a profound expansion into the Baltic north.

But beneath the optics of solidarity, the same old tensions never really went away. Instead, they evolved. In many ways, the war in Ukraine masked the deeper existential crisis NATO now faces: a transatlantic divergence in strategic priorities, a growing identity crisis, and the risk that political volatility within member states could tear apart decades of painstaking cohesion.

Diverging Threat Perceptions

At the heart of NATO’s tensions lies a question of purpose. For countries like Poland, Estonia, and Romania, the threat is clear and immediate: Russia. The memory of Soviet occupation is still raw, and the war in Ukraine only reinforces their belief that NATO must remain laser-focused on deterring Moscow.

But for Washington—and increasingly for London, Tokyo, and Canberra—the strategic horizon points eastward. China is the long-term concern: militarily, economically, and technologically. From AI to rare earths, semiconductors to space, the U.S. sees China as the only true peer competitor capable of shaping the global order.

The Biden administration, and even more so the Pentagon, has tried to pull NATO into a broader role that includes maritime security, critical technology coordination, and strategic dialogue with Indo-Pacific partners. The inclusion of Australia, New Zealand, Japan, and South Korea at recent summits signals this pivot.

Yet many European countries are wary. “NATO is a North Atlantic alliance,” a senior German official told ONN World, “not a Pacific patrol force.” France is especially vocal, arguing that spreading NATO too thin dilutes its effectiveness and legitimacy.

The Trump Cloud Returns

Hanging over every strategic conversation in Washington this week is the specter of Donald Trump. With polls tightening in the U.S. presidential race, the possibility of a second Trump term is very real. European leaders are preparing for it—not with hope, but with contingency planning.

During his first term, Trump famously called NATO “obsolete,” threatened to pull the U.S. out, and privately questioned whether America should defend smaller allies like Montenegro. This time, he may return more emboldened, more prepared—and surrounded by advisers intent on shrinking America’s global commitments.

The EU is quietly accelerating efforts to create its own defense capacity—through the PESCO framework, through increased funding for the European Defence Fund, and via bilateral arrangements led by France and Germany. But even its proponents admit: European defense without the U.S. remains aspirational at best, especially as the continent depends heavily on U.S. surveillance, transport, logistics, and nuclear deterrence.

Cracks Within the Democratic Core

While NATO likes to call itself a community of democracies, that self-image is increasingly at odds with reality. Hungary and Slovakia have elected leaders who echo Kremlin talking points. Turkey has repeatedly blocked consensus in NATO’s decision-making, pursuing its own regional agenda from Syria to the Caucasus to Libya. And far-right populist movements in France, Germany, and the Netherlands are increasingly hostile to both the EU and NATO.

This is more than a public relations problem. NATO decisions are made by consensus. If even one member vetoes an operation or enlargement (as Turkey did for years with Sweden), the entire alliance grinds to a halt.

A senior NATO diplomat described it bluntly: “The biggest risk to NATO is not Moscow or Beijing. It’s Budapest and Bratislava.”

Ukraine: The Alliance’s Unfinished Promise

Ukraine remains NATO’s greatest unfinished promise. At this summit, Kyiv will receive more military aid, a new round of long-term security guarantees, and possibly a formalized path toward eventual membership. But full NATO membership still seems distant, primarily because it would obligate NATO to go to war with Russia—a line most members are not yet willing to cross.

Zelenskyy, speaking at a closed-door pre-summit session, reiterated his position: “If NATO cannot defend Ukraine, what is its purpose?”

The question stings because it’s not just about Ukraine. It’s about the credibility of NATO’s Article 5 pledge: that an attack on one is an attack on all. If that pledge is seen as conditional, depending on geography or timing, it loses much of its deterrent power.

The Spending Gap: Persistent and Politicized

Back in 2014, NATO members pledged to spend at least 2% of their GDP on defense by 2024. In 2025, only 23 of the 32 members have met that target. While the U.K., Poland, and the Baltic states have exceeded it—Poland is now spending 4%—key Western European economies like Belgium, Spain, and Italy still fall short.

This disparity is more than budgetary. It’s political ammunition for those in Washington who argue that NATO is a one-way security bargain. Trump exploited it. So might others.

India and Japan, watching from the sidelines, have noted the irony: NATO demands commitment from its members but struggles to enforce internal discipline.

Global Partners and a Bigger Tent

Interestingly, the summit also features expanded dialogue with non-members. Japan, South Korea, Australia, and New Zealand have all participated in NATO’s recent strategic discussions. India, while still cautious, has sent observers to some informal consultations—a sign that even New Delhi sees value in monitoring the alliance’s evolution.

Russia, for its part, views NATO’s Pacific overtures as an encroachment—especially after Finland’s accession added over 1,300 km to NATO’s land border with Russia. China echoes that sentiment, calling NATO a “tool of U.S. hegemony under the guise of multilateralism.”

Whether or not these claims hold water, they are shaping the narrative in the Global South, where many nations remain skeptical of NATO’s moral authority—especially given its interventions in Afghanistan and Libya.

A Future That Cannot Be Assumed

For all the tanks, treaties, and televised summits, NATO’s fate may depend less on its hardware and more on its cohesion—on whether its members still see the world through a shared lens. That consensus, once forged in the Cold War, now faces new strains: competing threat perceptions, divergent political values, and widening debates over identity, purpose, and scope.

Europe wants predictability. Washington wants flexibility. The Baltics want deterrence. The Global South wants neutrality. And Ukraine wants membership. These are not incompatible demands—but they are difficult to reconcile under a single umbrella.

This week’s summit won’t answer every question. But it might be remembered for posing the right ones. Not just “how do we confront Russia?” or “should we speak about China?”—but something more fundamental: What exactly holds NATO together when the glue of the Cold War is long dried?

Seventy-six years in, the answer is no longer obvious. But history has a way of testing alliances just when they begin to doubt themselves. NATO, for all its contradictions, may soon find out what it’s truly made of—not in a summit hall, but in the unpredictability that lies ahead.