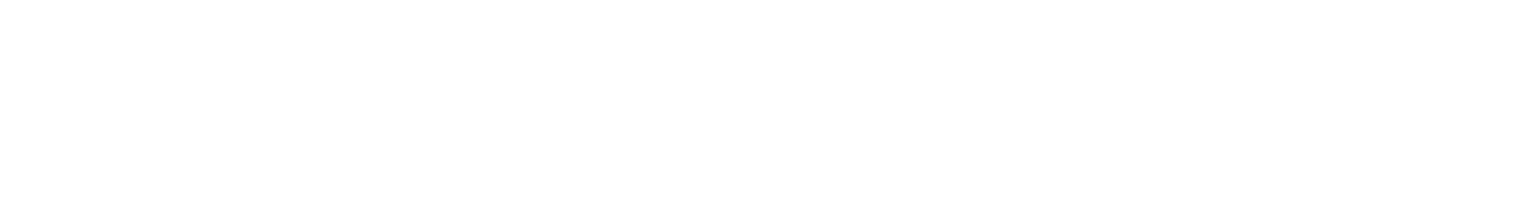

In a remark that stirred both domestic political currents and international interest, Arunachal Pradesh Chief Minister Pema Khandu stated on July 8 that “India shares a border with Tibet, not with China.” While seemingly rhetorical, the comment has deeper historical and geopolitical implications that challenge dominant narratives shaped over decades.

The statement comes at a time of heightened tensions along the Line of Actual Control (LAC), especially in the sensitive eastern sector of Arunachal Pradesh, which Beijing claims as “South Tibet.” For India, Khandu’s assertion aligns with a growing sentiment that Beijing’s territorial claims are built upon a forced occupation of Tibet, not historical legitimacy.

Reclaiming the Historical Lens

Before 1950, Tibet functioned with de facto independence. It signed treaties, had its own currency, and managed its external affairs. When Mao’s People’s Liberation Army entered Tibet in 1950, India protested diplomatically but stopped short of deeper action. In 1954, New Delhi signed the Panchsheel Agreement with Beijing, tacitly recognizing China’s control over Tibet. This would go on to shape decades of official silence regarding Tibet’s status.

Khandu’s comment appears to defy this diplomatic precedent. By asserting that India’s true neighbor is Tibet, not China, he underscores a larger truth: the cultural, spiritual, and historical ties between Arunachal Pradesh and Tibet go back centuries, far deeper than the geopolitical arrangements that followed Chinese annexation. The statement that India shares a border with Tibet is not merely symbolic—it is a geopolitical reminder of what was lost and what still might be reclaimed.

The Dalai Lama Factor

Adding complexity to this debate is the presence of the 14th Dalai Lama in India, who fled to Arunachal Pradesh in 1959 during the failed Tibetan uprising against Chinese rule. India granted him asylum, and his exile government still operates from Dharamshala. With the Dalai Lama aging, the question of his succession looms large—and with it, the possibility of Beijing installing its own puppet reincarnation.

This has become more than a religious issue. It is a political fault line. India has hinted, subtly but consistently in recent years, that it may not accept a Beijing-appointed Dalai Lama. Arunachal, which hosts the Tawang Monastery—a key site in Tibetan Buddhism—is likely to play a central role in the unfolding succession battle.

The Succession Controversy Deepens

On July 2, shortly before his 90th birthday, the 14th Dalai Lama reaffirmed that his reincarnation would be decided solely by the Gaden Phodrang Trust—the spiritual institution he leads. He also hinted that his successor may be born outside of Chinese-controlled Tibet, possibly even in India. This statement was a direct challenge to Beijing, which has insisted that the next Dalai Lama must be approved by the Chinese state under a centuries-old ritual called the “Golden Urn” system.

India’s Ministry of External Affairs declined to comment directly on the spiritual matter but emphasized religious freedom. However, Union Minister Kiren Rijiju—himself a Buddhist from Arunachal—backed the Dalai Lama’s authority in deciding his own succession, sparking strong reactions from China. Beijing warned India against interference and accused it of politicizing a religious process.

The likelihood of two rival Dalai Lamas emerging—one recognized by Tibetans in exile and another by the Chinese Communist Party—has grown stronger. Such a schism could further polarize global opinion and deepen the India-China rift.

From Strategic Silence to Assertive Posturing

India’s political approach toward Tibet has historically been cautious, shaped by a desire to maintain border peace and avoid provoking China. But in recent years, the calculus has shifted. The 2020 Galwan Valley clashes were a turning point. Since then, India has ramped up border infrastructure, reasserted control over sensitive passes, and amplified its public messaging.

Pema Khandu’s remark is part of this broader shift. It signals a willingness within Indian leadership, particularly at regional levels, to speak truths that New Delhi once avoided. The statement, while not official Indian foreign policy, reflects the growing domestic support for re-framing the Tibet issue as central to resolving the India-China border dispute. It reinforces the narrative that India shares a border with Tibet, a truth obscured by years of diplomatic caution.

A New Axis: India, the U.S., and Taiwan

The international context surrounding Tibet is also shifting. The United States has increasingly taken a firmer stance on Tibet, passing legislation such as the “Tibetan Policy and Support Act” and the more recent “Promoting a Resolution to the Tibet-China Conflict Act” in the U.S. Congress. These acts support the Dalai Lama’s right to determine his succession and affirm Tibet’s unresolved status under international law. Washington has repeatedly criticized Beijing’s interference in Tibetan religious affairs.

This growing alignment opens the door for deeper Indo-U.S. cooperation on the Tibetan issue. Strategic dialogue, joint support for the Tibetan exile community, and coordinated messaging on the legitimacy of Tibetan autonomy could become pillars of a broader geopolitical front countering Chinese expansionism.

Another player watching closely is Taiwan. Although the Republic of China historically claimed Tibet and Arunachal Pradesh as part of its own territory, the current leadership in Taipei may shift its position. In seeking stronger strategic ties with India and international legitimacy against Beijing’s threats, Taiwan could recognize India’s claims and Tibet’s unique status—turning away from outdated maps in favor of new diplomatic calculus. Such a move would mark a seismic shift in Asian geopolitics and deepen China’s sense of encirclement. It would also strengthen the strategic reality that India shares a border with Tibet, not with a unified or uncontested China.

Russia’s Balancing Act

Amid these realignments, Russia finds itself in a delicate position. As a founding member of both RIC (Russia-India-China) and BRICS, Moscow has an interest in preventing open conflict between India and China. A major flare-up along the LAC could weaken the cohesion of these multilateral platforms, undermine Eurasian stability, and distract China from its alignment with Russia against the West. While Russia has historically supported China’s sovereignty narrative, it may quietly encourage both sides to de-escalate, hoping to preserve its role as a strategic mediator and safeguard the future of RIC and BRICS as counterweights to Western blocs.

Looking ahead, Russia could also position itself as a quiet mediator—not out of idealism, but from strategic necessity. A stable India-China relationship keeps BRICS viable, RIC relevant, and ensures Russia doesn’t lose influence over two of Asia’s biggest powers. While Moscow is unlikely to get involved in the Tibet issue directly, it may act behind the scenes to prevent the situation from becoming a broader geopolitical flashpoint.

Beijing’s Historical Rejection

China, for its part, recently rejected the legitimacy of borders drawn by British India, declaring that it does not recognize the McMahon Line—upon which the current India-China boundary in the eastern sector is based. This denial adds further weight to Khandu’s assertion: if China does not accept British-imposed borders, then Tibet’s historical sovereignty—and its border with India—comes back into question. The CM’s statement, therefore, not only challenges Beijing’s territorial claims but also undermines the very foundation of China’s modern cartographic posture.

Global Implications

For the international community, the remark brings attention to a long-suppressed fact: that China’s western and southwestern borders are not based on natural geography or historical continuity but on military expansionism. As middle powers recalibrate their ties with both Beijing and New Delhi, the Tibet question may re-emerge as a geopolitical lever, especially among democratic alliances wary of China’s authoritarianism.

Ultimately, Khandu’s statement is not just a local politician’s rhetorical flourish. It is a crack in the edifice of diplomatic silence around Tibet—a reminder that maps, like narratives, are often drawn by the victors, but questioned by the persistent.