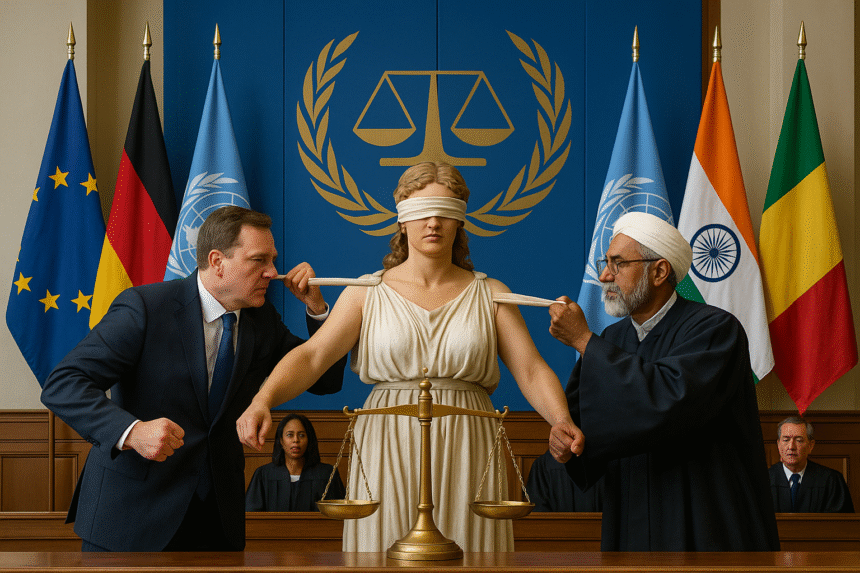

In courtrooms far removed from the devastation of war, judgments are delivered that echo across continents. Arrest warrants are issued, war crimes codified, and perpetrators named. But behind the legal formalism of international justice lies a deeper contest—one that is quietly reconfiguring the global order:

Who has the authority to define justice?

From The Hague to Harare, from Gaza to Georgia, the legitimacy of the International Criminal Court (ICC)—and the broader edifice of international law—is under growing scrutiny. Not just from autocrats and pariahs, but from constitutional democracies, legal scholars, and civil societies across the Global South.

At its core, the debate is not about the existence of justice—but about its ownership. Does the architecture of global justice reflect a genuinely universal ethic, or merely the geopolitical preferences of the powerful?

A Court for Humanity—or a Court for the Hegemon?

The ICC was conceived in 2002 as a triumph of international morality: a permanent tribunal to prosecute genocide, war crimes, and crimes against humanity—regardless of a perpetrator’s rank or nationality. It was heralded as a step toward a more accountable world.

Yet over two decades on, that vision remains unfulfilled.

Of the Court’s indictments to date, a disproportionate number have targeted African leaders. Figures from Sudan, Uganda, Kenya, and the Central African Republic have been summoned to The Hague, while perpetrators of major atrocities in Western interventions have largely evaded scrutiny. The architects of the 2003 invasion of Iraq, which claimed hundreds of thousands of lives, remain untouched. British and American actions in Afghanistan, Syria, and Libya are often excused as strategic miscalculations, not prosecuted as crimes.

When Western power is involved, justice seems to hesitate.

Even the Court’s most recent move—seeking arrest warrants for both Israeli and Hamas leaders—has been met with diametrically opposed reactions. The Global North condemned the equivalence. The Global South, for the most part, saw it as a rare step toward parity.

Geopolitical Justice: Selective, Strategic, and Sanitized

The contradiction at the heart of international law is not new—but it is growing more untenable.

In 2023, the ICC’s warrant against Russian President Vladimir Putin for war crimes in Ukraine was lauded in Western capitals as courageous. Yet when similar charges were brought in 2024 against Israeli officials over the war in Gaza, the reaction shifted—from applause to outrage.

Such hypocrisy has not gone unnoticed. For many in the Global South, it only reinforces a long-standing perception: that international justice is not blind, but blinkered—shaped by the contours of power, not principle.

In 2016, South Africa, Burundi, and Gambia initiated withdrawals from the ICC, denouncing it as a neocolonial instrument that disproportionately targeted African states. Though those withdrawals were later stalled, the disillusionment remains potent.

Where Justice Withers: A Catalogue of Global Inaction

Beneath the surface of tribunal proceedings lies a grim ledger of legal omissions—cases where justice has either been denied, deferred, or diluted:

- Iraq (2003–2011): The U.S.-led invasion, premised on fabricated intelligence, resulted in mass civilian casualties and systemic abuse. Yet no Western leader has been held accountable. The ICC opened a preliminary probe—only to quietly shelve it.

- Afghanistan (2001–2021): When the ICC attempted to investigate alleged war crimes by U.S. and Afghan forces, Washington retaliated by revoking the prosecutor’s visa. Under diplomatic pressure, the Court curtailed its inquiry, effectively shielding American conduct.

- Sri Lanka (2009): The brutal final phase of its civil war left an estimated 40,000 Tamil civilians dead. UN reports cite possible war crimes—yet no international tribunal has stepped in, and domestic accountability remains elusive.

- Yemen (Ongoing): Years of Saudi-led airstrikes—many targeting civilians—have left a humanitarian catastrophe. But Riyadh, shielded by powerful allies and flush with Western arms contracts, faces no meaningful investigation.

- Myanmar (Rohingya Genocide): Despite mountains of evidence, the ICC’s response has been glacial. With Myanmar outside its jurisdiction and China offering protection, international justice once again buckled.

This is not the absence of law—it is the selective application of it. And where selectivity persists, legitimacy erodes.

Justice in a Multipolar World

What we are witnessing is not a rejection of justice, but its reclamation.

As unipolarity fades and a multipolar order asserts itself, the Global South is demanding not just representation, but authorship. New legal frameworks—from the African Court on Human and Peoples’ Rights to BRICS legal task forces—are emerging as alternatives to Western-dominated institutions.

These entities don’t dismiss the concept of accountability—they reject a system where accountability flows in one direction only.

This is not about undermining the rule of law. It’s about challenging the monopoly over lawmaking and lawkeeping.

The ICC’s Existential Test

For the ICC, the stakes are existential. If it fails to demonstrate even-handedness—if it remains structurally tilted toward the interests of dominant powers—it risks becoming obsolete.

Can it prosecute with courage when powerful states are involved? Can it develop enforcement mechanisms independent of Western military or political will? Can it survive without capitulating to the very forces it claims to regulate?

These are not merely legal dilemmas—they are questions of political integrity.

Because at its heart, the ICC was meant to embody a universal ethic. If that promise continues to be compromised by expediency, then it will not be reformed. It will be replaced.

Redefining Justice

The fundamental question is no longer whether international justice can work. It is whether it can be redeemed.

Justice cannot be built on impunity for some and punishment for others. It cannot survive as a hierarchy disguised as a principle. If it is to endure, it must reflect the plurality of moral voices in the 21st century—not just the self-assured conscience of the post-World War II West.

We do not live in a post-justice world.

But we do live in a post-Western world.

And the institutions of global governance must now decide: will they evolve with history—or be overrun by it?